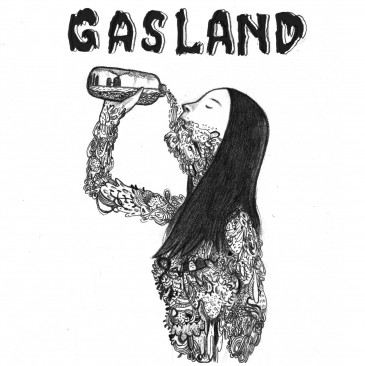

Josh Fox does not want his drinking water poisoned. Fair enough. Schooled in the documentary tradition of Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock, Fox constantly inserts himself into scenes in his film. The outcome is awkward, but effectively demonstrates that this movie is a personal plea. Slightly self-indulgent, the film brings attention to the much-needed conversation around natural gas extraction. Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to recap, is the process used to extract underground natural gas deposits (the film focuses on shale gas). Companies drill into the ground, chemicals and water go in, a small earthquake occurs and gas comes out. The film is especially relevant here, given that Northeast British Columbia has the biggest source of shale deposits in Canada and natural gas production is already well under way in the Peace River region.

The film is a journey into the “heartland of America” in which the protagonist, our good buddy Fox, discovers more and more about the insidious effects of natural gas drilling. After a gas company offers to lease his land in Milanville, Pennsylvania for $100,000, Fox goes on a nauseating road trip filled with dead animals, brain lesions and contaminated water to find the effect of fracking on residents living near well sites.

The film’s central concern is specific to the regulations put in place in the United States in 2005. An exemption in the Safe Water Drinking Act means that companies can claim the chemicals they use as trade secrets rather than being forced to disclose the “secret sauce” that they pump into the ground. So if a water source is poisoned, it is extremely difficult to trace the exact source of what is making people sick and even more difficult to regulate practices. The Fracturing Responsibility and Awareness of Chemicals (FRAC) Act that Fox discusses in the film is a bill to have fracking included in the Safe Water Drinking Act, but it has been blocked in congress several times.

In B.C., companies have to disclose their methods; fracfocus.ca provides a list of all well sites and the chemicals used during fracking. Still, companies do not have to list the chemicals until 30 days after drilling has begun, so the approval process for companies is unaffected by this information. On top of this, there are still many other issues with fracking, including water use, carbon emissions and the fact that despite monitoring, contamination from drilling and above-ground spills still happens in Canada and the U.S.

Ironically, Fox would actually benefit from fracking in a way most Canadians would not. He would actually get paid to lease his land, whereas in Canada the mineral rights for land beneath the topsoil mostly belong to the government. Here, you could have a drilling site right next door and not see a penny. Fox would at least get $100,000 at the risk of being poisoned. Gasland is a visual journey through the American natural gas industry. The road movie format is effective, but it might be time to turn the car around and head north.