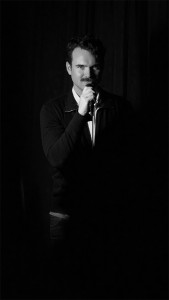

Since moving to Vancouver seven years ago from small-town Alberta, Cole Nowicki has devoted himself to various literary and creative realms throughout the city — comedy, poetry, design, and plenty of work in between. It’s no surprise that Nowicki’s most recent project, fine., has generated such well-deserved enthusiasm from the get-go. The monthly event, distinct in its emphasis on storytelling, has drawn an audience from every corner of the city — a reach that has extended well beyond just the literary community. With performances from a diverse pool of local comedians, poets, writers, and musicians — like hazy, Mourning Coup, and Milk — fine. offers a story for every listener. “There’s a lot of cool stuff happening in Vancouver, but I wanted to get a little weirder, so I set up a platform for myself and other standups and storytellers and writers. There are a lot of talented folk,” says Nowicki.

Moving onto its fourth event, fine. has pulled in a full crowd each night, with transfixed listeners leaning in from floor seats, couch corners, and clustered chairs, slunk back among friends and plenty of beer. Nowicki explains, “It’s a good atmosphere. It’s cozy. In terms of a storytelling event, it’s a comfortable space, [and it’s] where my friends and I go hang out regularly, so it’s familiar.”

Despite the Lido’s centrality and treasured appeal, fine.’s popularity transcends familiarity by breaking unique ground. “I think the reason why it tends to be popular is that there are people from all different realms,” Nowicki concedes, “comedy people, people coming to see the stand up acts, the writers, the bands that play … That’s what helps with having a diverse group of performers: they’re gonna invite their friends, their friends are gonna invite their friends.”

Beyond the charm of fine.’s always-eclectic lineup, it’s Nowicki’s allowance for spontaneity that imbues the show with palpable authenticity and ease; there’s never a sense of urgency, nothing formulaic or prescribed. At fine.’s January event, Nowicki and writer Ben Stephenson both shared stories which pivoted thematically on the taboos of gay skate culture. When asked whether it was by design or sheer coincidence, Nowicki recounts that the correspondence was totally unplanned, explaining that the two pieces just “dovetailed into each other.” He insists, “One of the things I really like about doing a show, is that when I get to do my piece, I’m doing whatever the hell I want, so I like to give everyone on the show the same opportunity … to branch out and try something different.”

Nowicki kicks off each show with a piece of his own, setting the bar for anything goes. “I had this story … where I found out a couple years ago that my dad’s cousin is a New York Times best-selling romance novelist.” At my confusion, Nowicki clarifies, “She writes erotic novels. [She’s] sold like, millions of books … I was inspired, because I wasn’t really getting anywhere with my personal writing, so I thought, ‘I’m gonna try to get into the erotic novel realm, and I wanna write what I know, and what I know is skateboarding,’ so I read a piece of skateboard erotica.”

While charming and casual in his role as host, Nowicki is nonetheless staunchly committed to cultivating a sense of community: “I have a bit of a particular vision, but storytelling is pretty universal in its appeal. People like to share in others’ shared experiences, people like to laugh. And I’m pretty happy that people are coming to the show … and enjoying it.” fine., it would seem, is on its way to big things: “I bought a standing lamp, so it’s not gonna be that weird stacked light anymore. Three shows in — proper lamp. Yeah, we’re getting legit,” he laughs.

When he’s not skating, writing, or picking out light fixtures, Nowicki dips his toes in other creative realms, like designing an illustrated short story project, Portraits of Brief Encounters, and working on short story submissions. Reminiscing on his first brushes with the Canadian literary community, Nowicki shares, “I would write poems and submit them to little journals that I’d find online, magazines I would get in the mail. I was probably 17 or 18 when I first got published … I had to get rejected [a lot, but] I’ve been skateboarding since I was 11 or 10, so I’m used to not getting things very quickly. You know, you fall down and eat shit, and then just keep trying until you get it.”

Looking forward to fine.’s next events, Nowicki raves that “everyone has killed it so far. I’m just grateful that most of the people who’ve been on the show and performed do not know me. I just out of the blue ask them to take a chance and be on the show, and they do, and I appreciate that. I’m grateful to be able to do something that I wanna do, and that other people seem into it.”

X

fine.’s next installment takes place April 24 at The Lido, and won’t be one to miss. For more information, visit afineshow.com or follow @afineshow on Instagram.