“It was a terrible, terrible thing to point him out among all those cons, but I didn’t think about that then,” Cash said later in an interview with Time. “Everybody just had a fit, screaming and carrying on.”

Most of the 224 pages in Reinhard Kleist’s comic book biography lead up to the Folsom concert and the moment when Johnny Cash, 6’2″ and millions of records strong, leaned down offstage to shake the hand of a man in prison clothes who couldn’t help casting his eyes to the floor.

The way Kleist tells it, in black ink and with Sherley narrating, Cash’s life looks shades darker than it did in Walk the Line, the 2005 biopic that centres on Cash’s marriage to June Carter. Kleist’s take is positioned in even sharper contrast with Hello, I’m Johnny Cash, a colour comic put out in 1976 by Spire Christian Comics to shepherd young rockers from sex and drugs to regular churchgoing. In one panel, a man runs out of a bright-lights Vegas casino yelling, “Johnny Cash is in there and he’s singing about Jesus!!!”

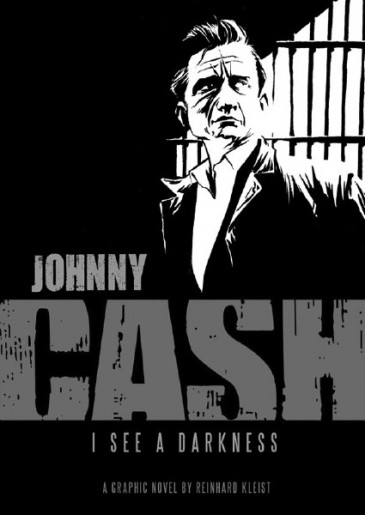

Kleist, a German graphic designer with a studio in Berlin, has a proven eye for phantasmagoria. His comics include the Berlinoir vampire series, a biography of H.P. Lovecraft and Amerika, a wordless travelogue by a mute dwarf who lives within the New York underground. The way Kleist draws him, Cash is always The Man in Black, playing every gig in black jeans, a black jacket and an open, pointed collar.

Not only does he shade out the rhinestone cowboy outfits of Cash’s early days, Kleist passes completely on what became Cash’s biggest undertaking of the 1970s and the highlight of the Christian comic: a feature-length film shot in Israel with a matching double LP in which Johnny drawls the story of Jesus Christ.

But if Kleist tends toward the darker episodes of Cash’s life, it’s not for lack of material. Kleist’s noir style suits Cash’s hard living days, days when he had burned through his first marriage with booze, amphetamines and one-night stands. Kleist lets the pages go to black when the troubled star nearly kills himself in Tennessee’s Nickajack Cave, and later splits Cash’s body into a tangle of lines and glass shards as Cash finally kicks his drug addiction with self-induced withdrawal.

Still, an edgy, noir vibe is not all that Kleist’s comic holds over Hello, I’m Johnny Cash. Kleist punctuates the gospel of Johnny—floods on the cotton farm, lights in the cave—with a set of vignettes that imagine, in very different styles, the songs “Folsom Prison,” “Big River” and “A Boy Named Sue.” Some work better than others. But the kind of biblical psychedelia Kleist draws into his “Big River” sequence and, in the epilogue, a sequence drawn from “Riders in the Sky,” goes a long way to explaining why this book won the highest awards for a graphic novel in Germany and sold out its first English-language print run.

And if Kleist sometimes draws an iconic Man in Black at the expense of a fuller, more detailed picture of the real-life Cash, the book does draw attention to a part of Cash’s story that is often overlooked—the sad fame of Glen Sherley, who shot himself years after he won early parole, a job and a few records, by sending a song to Johnny Cash.

Johnny Cash: I See a Darkness. Abrams Comic Arts, 2009. By Reinhard Kleist