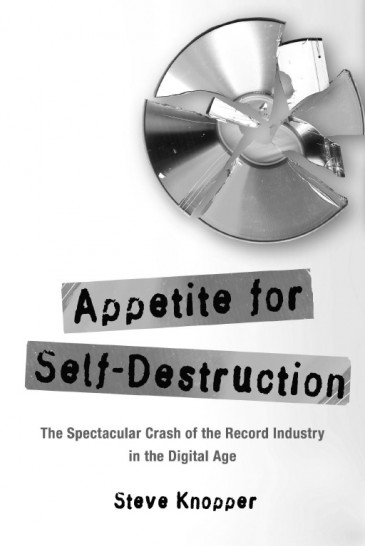

Author Steve Knopper, who now freelances for the likes of Spin, Wired and Rolling Stone, fittingly got his start writing obituaries. This colourful obit takes him deep into the dark hearts of CBS Records, Sony, Warner and Universal Music, labels where the top brass were too moneyed, too lawyered or too afraid to kick their core business of selling shiny plastic discs.

In the course of seven, character-driven chapters, Knopper lists off eight bullets that sent the industry spinning: the CD “longbox,” pay-for-play radio, wiping out digital audio tapes and killing the single, the RIAA lawsuits, the Sony BMG Rootkit and whiffing on their own plan to sell music digitally before the advent of iTunes.

It’s no wonder that HBO has optioned the rights to make this book into a feature-length film. Knopper himself suggested something along the lines of Boogie Nights, a good match given that both star the Internet in a killing role and feature a cast of characters who appear larger than life. Walter Yetnikoff, the CBS Records man responsible for the success of Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” enters the book as a “coke-addled, fast-living, bomb-throwing, disrespectful provocateur.” Tom Freston, “one of the brain trust of frustrated and slumming music-business types,” who created MTV, gets a typical summing up as “an advertising executive who’d worked on the G.I. Joe account before fleeing the toy business to hike through the Sahara with a girlfriend, then landed in Asia to run a fabric-export company.”

Not only HBO producers, but also music and business critics have praised this book, usually with the one holdout that it sometimes reads like a cartoon. I think it’s fair to say Knopper sides a bit with his supporting cast, underlings like the nuclear physicist and audiophile James T. Russell, a guy who unsuccessfully tried to shop around a prototype CD player that he single-handedly built in 1965 after learning that vinyl records will scratch and hiss even if you play them with a cactus needle. Knopper does set up a good guy/bad guy dynamic where young, penniless programmers—the Fraunhofer team who first coded MP3 files and or even Napster’s Shawn Fanning—get nowhere when they try warning or working with big music labels to prevent their impending online doom. On the other hand, Knopper seems to share some sympathy with the label execs who feel that Steve Jobs cut them a hard deal when he gave them just 67 cents per track sold on iTunes.

If it’s a bit cartoony, the pages of Appetite for Self-Destruction flip faster than the Nana Mouskouri section in the Sally Anne. And it’s not every label exec who comes off looking like Sony’s $10-million-in-yearly-expenses Tommy Mottola. One of Knopper’s best chapters reads like an ant versus grasshopper fable between the two champions of the 1998-2001 teen pop bubble: Backstreet Boys producer Clive Calder, who smartly retired his family to the Cayman Islands after keeping his own costs low, and Backstreet Boys creator Lou Pearlman, who now lives in jail after losing ‘N Sync and getting caught racketeering.

Like a good investigative reporter, Knopper follows the money trail, detailing how labels continued to deduct vinyl-era “packaging” fees from artist’s CD royalties, illustrating how Walmart and Best Buy were allowed to take over 65 per cent of U.S. music sales, and showing righteous anger over how the labels managed to fix CD prices at more than double the average $8.99 cost of a vinyl LP, even when they were several times cheaper to produce.

After all the bad deals and worse music the big labels made, the final chapter ends by pointing to a more positive future. Radiohead’s pay-what-you-can In Rainbows release gets a mention, as does Madonna’s break with labels in favour of a touring company. Knopper sides with Wired editor Chris Anderson’s “Long Tail” vision, where consumers quit collecting songs and instead subscribe to unlimited back catalogs.

The best quote on the music industry’s future comes from Mark Williams, a long-time A&R rep at Interscope Records. “It’s going to be like in the ’50s and ’60s when you had hundreds and hundreds of small labels,” he said. “It’s going to be a lot of trial and error. None of us know whether it’ll work right. I laugh when people say, ‘We’re going to try to fix it.’ They can try, but there’s no real answer. It’s over. It’s just done.”