Cora: Can you tell me your name and pronouns?

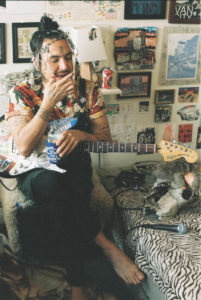

TJ (They/them): My name is TJ Felix, I don’t really have pronouns, but for the sake of brevity, they/them I suppose?

Cora: How did you get started in music in the first place?

TJ: I mean, I hated music till I was 11 or so. I loved RPG music — I was obsessed with video games, that was my one solace growing up. Music was always on because I lived in a party house, my dad was a drug dealer and there was music on all the time, so I had mostly negative connotations with music until I was about eleven.

I used to dig in the Malakwa town dump where I grew up — a side of the highway fuckin’ nowhere place. That’s where I felt safe. I liked to be there. To this day it’s solace for me, being able to dig through garbage and shit. Anyway, I found my first guitar in the town dump, it was an acoustic guitar with three strings. Everything I do is self taught, it’s an outlet that quickly became necessary for survival. I was never informed by any colonial standards for art or anything. It gives me an appreciation for everyone. [We’re] put into these rigid categories and taught standards and practices from old white dudes. People learn all the scales and shit — it just conditions you to emulate that, I feel. I didn’t even know what tuning was, I just thought it meant either you like your strings loose or you like your strings tight.

Cora: I love that so much.

TJ: Soon it became this constant treasure hunt for music. I used to have to walk along the highway to get anywhere —living in the middle of nowhere, it took like two hours along the highway, or through the forest, or down old dark roads to get anywhere. Back in the day, you would just find random fucking CDs along the side of the road, and meet the weirdest people. I don’t know, music sharing was so different. I’m 33 so I’m ancient. We didn’t have the internet, so if you were passionate about music, there was a reciprocal communal aspect to it. We were hardwired for it because of the horrible living conditions we were in. That is still at my core, like, I can’t do things remotely. I can’t work on computers that well because I have ADHD, so I think it is a strength to sit with people and share things — in a way, that’s humanizing. Obviously COVID wasn’t very good for that, I was working a community education job during covid, and it was all remote, it was so unnatural to me. I go on tangents, as you can tell.

Cora: I think it’s important to capture these rambling thoughts about how you get to somewhere, it’s all part of it. It’s all part of that story right.

TJ: Yeah, I love to talk, what can I say?

Cora: Well you wouldn’t be a musician if you didn’t have things to say, right?

TJ: Yeah, musician, but also a raging egomaniac.

Cora: So you taught yourself how to play, who did you teach yourself to? Who did you play against?

TJ: I have a vivid memory of my dad kicking in my door when I was listening to Linkin Park and playing air guitar, and it was really embarrassing. The first song I played on guitar, I think, was “Stairway to Heaven” Maybe, ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction? . Nostalgia is a hell of a drug. Blink 182 was my favourite band, or like, NOFX, you know, just like shitty skate punk. They’re shit dudes but good song writers. I mean, I’m biased, I think nostalgia affects everyone. There’s no such thing as an objective truth, so nostalgia is an important factor when it comes to my influences, like Hellcat or Rancid or even Epitaph. For me there are no guilty pleasures. I think the first instrument I really got any good at was drums, back in first grade. We were all playing the recorder, and I wasn’t able to do it. My brain just wouldn’t adapt to the public school model… it never managed to. I would be up on the snare drum, in the corner, and all throughout school I played drums. Before I was really into music, I thought of it more like a sport. It seemed like something people were using to validate themselves in the eyes of the instructors. Using their bodies in a way that was different from sports, but similarly exploiting it. I guess I just wasn’t really into playing classical music or being told what to play.

Cora: I was listening to the album you dropped the other day, Songland, and I heard influences from Rob Zombie, and Arcade Fire’s Funeral.

TJ: Rob Zombie! The Twisted Metal OST was all Rob Zombie. That game was a pretty big deal for me. During a certain period of my life I was playing that game a lot. I wouldn’t say Rob Zombie has been a conscious influence or anything for a while. When I was living in Vernon, I found a CD wallet on the side of the road while walking home from school.

Cora: An incredible find.

TJ: It had Arcade Fire, Broken Social Scene and the first Yeah Yeah Yeah’s EP. It made me wish I knew who it belonged to, because there wasn’t much community in the interior for weirdos — or however you want to put it.

Cora: Yeah in my hometown it was just me and my friend Steven, everyone else thought we were weirdos.

TJ: I had a few friends who would come up to see me in Vernon, we had a band that was just us getting really high in the basement and recording it all. Never actually writing full songs. My one friend would bring his trombone, and the other friend was a bassist. I would just detune my guitar in a weird way. We called ourselves Various Other Anti-Bodies.

Cora: Tell me the story of your first album.

TJ: It’s weird — I feel like other people don’t deal with this, I learned how to [write and] record with Audacity. It’s interesting to see my own progression, how I was teaching myself and learning at the same time. Especially with vocals — I’m still not very good at singing, that’s the hardest instrument for me. The first album I tried to release was called… something really long and pretentious. I’d email my songs to myself and use a computer in my school library to burn the songs onto blank CD’s. I called myself A NAM ENOLA, which is ‘A Man Alone’ backwards, you know, back when I still thought I had to call myself a man. Yeah, 2005. Rough times. I couldn’t give the things away, I just gave them to all my friends, and no one listened to them at all. Kinda the same as now, but it’s getting a little better. That should never be the reason you make art, well, I don’t know. I always tell people I make art because it’s a job, but it wasn’t a job for years and years. Not until recently., I have been working so hard for something I never thought people would be interested in. I had to beg, steal and borrow just to make the art I needed to survive. Art’s always been harm reduction rather than a mode of communication. And everything is always in flux, that’s why I feel weird about interviews — everything is always changing, and you need to be aware of that, and learn from yourself. It’s a shame this world doesn’t foster or encourage that change. If there is such a thing as objective truth, it’s that everything is always in flux.

Cora: A hard part of doing interviews is trying to capture a moment that is inherently over by the time you get it on the page.

TJ: That’s very true, yeah. I feel like that’s futile. I mean, it’s also on the person that’s witnessing or observing, whether it’s an interview or a piece of writing, but it’s important to acknowledge all the chaos that we are trying to embody. That this is a historical document, rather than a manifesto. Unless it is a manifesto. It tends to be an expression of the culmination of things that have led us up to a moment in time.People really want things to be black and white, to understand people, but it’s impossible to understand people. I think it’s a great pursuit to want to know someone, to try to understand someone. To really commit yourself to that is to care and love for someone — and I think that is something people don’t have the time or energy for. It’s intentional that people have to work and do things just to survive, and they have little to give after the state has sucked them dry, it’s a shame.

Cora: One thing I’ve found, during interviews and in my life generally, is that people make music to help people they once were — to give the help they had needed earlier.

TJ: For sure. That’s something I haven’t fully unpacked for myself yet. I find it really odd looking back at stuff like journals and sketchbooks. My influences, and all the things that brought me joy, saved my life in a lot of ways. Especially seeing other comic artists, or artists in general, who have dealt with their own trauma, abuse or substance use — but there was like, next to no indigenous people talking about those things that directly impacted me and my family… I told myself, “I’m going to make this comic, I’m going to make this album, I’m going to really try to let it out, and then I’m going to kill myself.” Then I released the album and the zine, and people in the downtown eastside got a hold of them — and that’s my community. That was the first time I really felt seen and heard. It was really validating, and I hadn’t really had that up to that point. You know, dealing with trauma and being open about it — being told my stories resonated and had value in a community. For ages, I couldn’t speak about any of it, because it felt like I was taking up too much space, or no one would get it. I was internalizing everything, poisoning myself constantly. It’s crazy that it felt great to do things in the name of killing myself, that it was easier in my mind to do that than to actually just speak to people. It’s wild that that’s something that trauma really does. It sounds bleak, but at the same time, as artists, I think having to navigate and process the world with the lens we have, we’re able to experience depths of beauty people don’t typically get to experience. At least that’s what I tell myself. It’s a brutal world, but there’s beauty in it still.