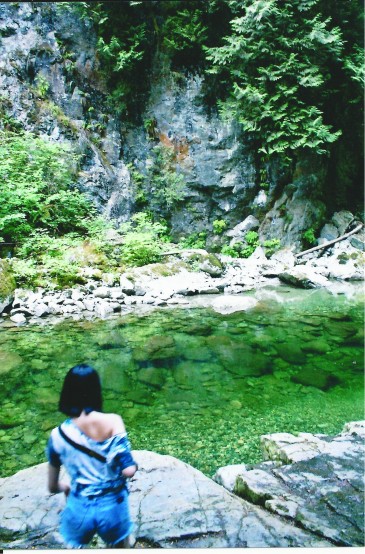

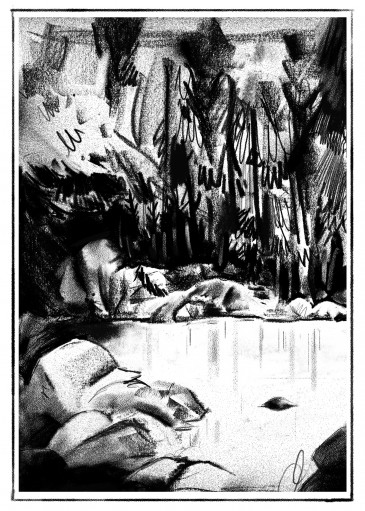

We all knew Lynn Canyon was dangerous. Exhaling swirling curtains of mist into the Valley, a hundred shades of green, sounds of rushing water and boiling cauldrons of hollowed rock throughout the rainforest. Fern grottos; waterfalls; humans? Inconsequential.

Lynn Canyon was always right beside us, waiting patiently for our next visit. We always felt safe in the forest, and sometimes, you could feel it loved you back. We locals felt immune to the dangers there. Anytime we heard news of the latest accidental death, we felt sorry, but smug. “Can’t be a local. Had to be from Burnaby or Surrey,” we’d mutter reassuringly to ourselves and each other. Any longer than a few minutes in the water, a jade-green vortex, and you’d be paralyzed; even in a hot June, it’s dangerous. The water runs high with frigid snow-melt.

Stand on the warm rocks and jump into the swimming hole on the hottest summer day you can imagine. Plunge down quickly through the translucent green and before you begin to rise up again, feel the instant chill that penetrates deep into your bones. Bet you’ve never felt your bones inside you before, have you? Well, you do if you jump into the water in the Canyon. Once you feel that true cold, you never forget it.

The knowledge is passed down from one generation of kids to the next. Older siblings and friends teach the younger ones who watch and wait. Adults don’t understand. They forget that when you’re young, you need a place to be away from the grown ups. It’s always been like that in the Canyon.

If you respect it, and are careful, you can survive its challenge, and it will help you to grow up. But the Canyon is as whimsical as its sparkling waters. Mostly unforgiving of error, stupidity, or insolence; sometimes it protects the foolish, like that drunk girl who flipped over backwards off the suspension bridge and lived. Other times it forgets its code or makes a mistake, and some innocent’s luck runs out.

Like the day Jacquie died — but that came later.

When we moved up from Pasadena, my sister Annette made four very good friends. Marnie was the most serious of the group, but good fun. Jennifer was petite and adorable with a sweet face; her outgoing, friendly personality made her everyone’s darling. Marion was the forthright red-head, and a seriously-good highland dancer. My sister was a spark, fearless and willing to try anything, even if it might be dangerous — she sent me a letter the year I was away in Quebec with a picture of her new punk haircut, the first of anyone we knew.

Jacquie was singular; kind and funny, freckle-faced, friendly and good-natured. Effortlessly graceful and athletic. Golden brown hair with summer streaks of light. Beautiful eyes: intense, very blue, with dark lashes. The way they looked at you, you could see depths.

All five girls were young and beautiful and growing up between the ocean and mountains in North Vancouver. They romped through school, “All for one, and one for all!” When you forge a bond that early, it’s virtually unbreakable. The Five Musketeers did everything together, including one of their greatest adventures: the movie.

Dennis Hopper ended up making a movie here called Out of the Blue and he needed some local kids to act in a classroom scene; it was the girls’ drama class they used.

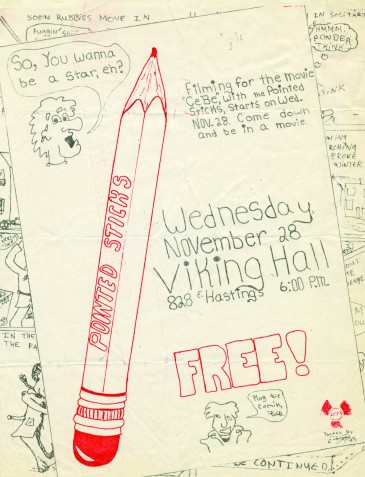

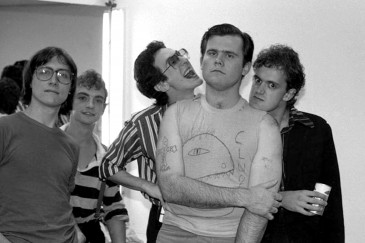

The movie adventure was exciting for a couple of reasons. Our hometown heroes, singles-band extraordinaire, The Pointed Sticks, were in it playing a “punk” band and performing “Somebody’s Mom.” But also, being in a movie with all of your friends was just a big thrill. Nothing like it had ever happened in Vancouver before.

Back to the Canyon. Just about every North Van kid spends a summer or two almost exclusively in the Canyon, and the Five Musketeers were no exception. The jumps at the big pools are two levels: one is scary, while the other higher jumps are dangerous and truly terrifying. No one jumps before seeing their older friends or siblings demonstrate the proper technique, because there’s a risk. You need coaching from the bigger kids who have survived. Experience necessary.

A moment’s hesitation, the leap, followed by a timeless freefall and the sudden, frigid plunge metres deep into a green abyss. Then hopefully, up again towards the light, through the froth of bubbles churned up by your torpedo body on the way down. Burst through to the surface and you’re alive.

Annette used to jump and — not long ago — she told me about the last time. It was from the highest jump at the 30-foot pool, never for the faint-hearted. She’d done it before, so she knew exactly how far you had to launch yourself, with an emphatic push as you leapt to clear the rocks. That day, she must not have taken the running start she should have, and she felt the feather-soft whisper of the rockface brush her spine on the way down. After that, she figured she had tempted fate enough and substituted the safer sports of parachute-jumping and mountain-climbing instead.

Jacquie hadn’t even been jumping that day. August 20, 1982. She and Marion had come down to the water to sunbathe. They lay stretched out in their bikinis, on the rockpile at the north side of the pool. Feeling sun-lazy and relaxed, absorbing the warmth from both sides — the sun above and warm rocks underneath their beach towels. Lifting their heads occasionally, lazily, as the irregular sound of jumpers entering the pool roused them back to partial-alertness.

It happened almost before Marion could realize what was going on. Jacquie must have been dozing in the sun as Marion noticed a big rock tumbling from above to where the two girls lay prone. Who knew if Jacquie even heard or saw it. Marion told Annette later that it was impossible to see where the rock was coming from or where it was going to end up. It was more the sound of it that you could distinguish, tumbling closer, and it sounded huge. Faster than Marion could act, it had already rolled past and into the water.

But it had struck Jacquie on its way. Marion, a lifeguard with all of her First Aid training, rushed to Jacquie’s side. Jacquie was lying where she had been sunbathing and looked untouched and perfect, but then Marion noticed that Jacquie had gone completely white; the rock had hit Jacquie right in her mid-section.

In the minutes that seemed like eternities, Marion stayed beside her friend, until the sirens began to wail outside the Canyon. Someone must have sprinted up to the suspension bridge and over to use a phone, but it was already too late. Jacquie was 19.

I don’t know if there is any lesson to this story, except that it kind of makes you wonder about the way things all seem to come together sometimes, for better or worse, unplanned and unanticipated, then crystallize, right out of the blue, into one defining moment to your whole life.

We think of Jacquie every time we cross the Lynn Canyon Suspension Bridge. Kids still use the canyon the way they always have. The other day, I was walking my dog on a trail my teenage nephews showed me. The summer morning was bright with slanting sunlight, and the night before had been warm and perfect for a bush party. I was the first person on the path that day; I could feel the cobwebs breaking across my face as I walked. A hundred metres into the forest, my eye was drawn right into the forest by a flash of metal. Wonderingly, I took in the tableau: a fallen log at the side of the trail, about a dozen empty beer cans, a crumpled package of Players, and a still-smouldering campfire. It was all laid out, as though waiting in readiness for the imminent return of the revelers.

I left it exactly as I found it: perfect. Perfect youth, forever.

Dedicated to Jacquie Whittaker