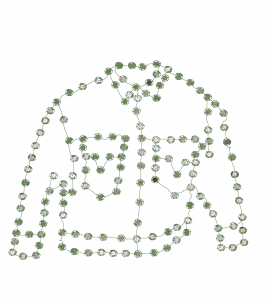

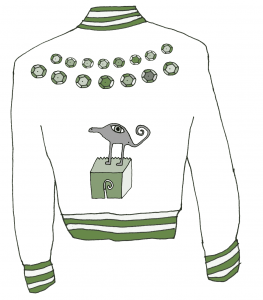

Harman, from the Carrier Wit’at Nation, and currently living and working in Coast Salish territories in Vancouver, effortlessly weaves punk aesthetics and ethos into their experiences of Indigeneity and self-identity through their work. “The bridge, in this case feels really natural to me,” they say, “like, to me, Buffy Sainte-Marie is the most punk ever. She’s The Grandest Auntie.” One of their more recent works, Potlatch Punk — shown as part of aceartinc’s exhibition “Oneself, and one another” in Treaty 1, Winnipeg last summer — showcases this juxtaposition explicitly. Harman’s piece consists of thrifted leather jackets carefully altered through embroidery and beading — coyote teeth, horsehair and beads, along with texts like “OUR BLOOD RUNS THE REDDER” and “TELL ME ABOUT FIRST CONTACT” adorn the garments — imbuing the very fabric of a typically punk signifier while subverting colonial erasure. “Right now, being able to show who you are as an Indigenous person and rolling up in your best beads, ready to say ’No’ to an injustice is so powerful because it shows how much you love your identity and your people.”

The jackets, displayed hanging in the centre of a white-walled exhibition space, aren’t necessarily reserved for that gallery format — “I definitely wear them sometimes!” says Harman — but you won’t see them being sold off any time soon. “I really hate this sentiment that once people see that you can make something, it’s immediately assumed that you’d be chill with selling it. I don’t mind sharing the jackets by showing them, and I do collect exhibition fees for doing so, but right now they need to live with one another and I don’t foresee that changing any time soon,” says Harman. But the question of ownership over the jackets extends to the wearer as well — and Harman is careful with who they allow to don them. “It matters a lot who wears them; I wouldn’t feel comfortable letting someone I didn’t have a good relationship with wear them, or someone who isn’t Indigenous,” says Harman. “It’d kill me to think of them in some private collection, probably owned by someone who isn’t Indigenous and would never understand the parts of myself and my family that I put into that work… The dream is to one day have the people I think of most often when I’m working on them dance [the jackets] into a space as a way of honouring the things they represent to me and to give respect to them as well.”

While Harman’s Indigeneity is integral to their artistic practice, not all of their work is intended for Indigenous eyes. Harman’s text work, part of their grad project at Emily Carr University of Art + Design, is usually for non-Indigenous folks, “but I think Indigenous folks usually get a kick out of it,” explains Harman. “The first iteration of that text work came entirely out of pettiness,” Harman admits. Visually dense and cumbersome to read, the short poem-like texts take express effort to decipher, “and then the ‘punchline’ in figuring out what it says isn’t always cute.”

Initially created during the events of Truth and Reconcilliation Commission, “I was so fed up with explaining myself and being held for all Indigenous politics, and being expected to spill everything out on command,” says Harman. “While I was hearing the full details of residential schooling for the first time from people back home who made the trips down to Vancouver to tell it, I was already expected to be an expert on it instead of expected to give myself time to process those things and [how] knowing those things affected how I understand the hardships in my community.” Coming from the Carrier Wit’at Nation located in Northern BC, Harman expresses their gratitude in being able to live, work and form community within unceded Coast Salish territories. “I’m an uninvited guest on these territories, but at the same time, the people I’ve met here have been so welcoming and empathetic,” explains Harman. “A lot of my work is shaped by that relationship of really feeling invested in and cared for by the people and this land, but also about missing my own home.”

Part of that sense of belonging in Coast Salish territories is the artist residency program at Skwachàys Lodge, an Indigenous art gallery and hotel, where Harman currently lives. “It’s amazing to have affordable housing in this city, not having to spend more than half of your monthly income on rent,” they say. “It gives you time to work towards building up bodies of work or applying for different opportunities and building better relationships in your community, just because you’re more available as a person.” Even with the benefits of the Skwachàys Lodge, Harman has mixed feelings towards it.

In addition to the neighbourhood in which it resides, on the border between Chinatown and the DTES — “[It’s] a hard place to be in, especially if you carry your own trauma. I don’t always feel tough enough to be in it,” — the many and sometimes conflicting layers of authority at the Lodge can encumber the ability of the artists within to work freely. “It takes a lot of negotiation to be comfortable in the building,” explains Harman. “You’re  dealing with the Vancouver Native Housing Society, the hotel management … building management, whose focus is split between us and the subsidized housing across from us with way more residents, and the gallery management; there’s a lot of bureaucracy and meritocracy.”

dealing with the Vancouver Native Housing Society, the hotel management … building management, whose focus is split between us and the subsidized housing across from us with way more residents, and the gallery management; there’s a lot of bureaucracy and meritocracy.”

The idea of punk, for Harman, extends beyond aesthetics, permeating throughout their practice in a multitude of ways, not just within the cultural mashup of Potlatch Punk, or their subversive textual response to the expectation of educating non-Indigenous people. “Punk is also, to me, about sharing; your time, your resources and your empathy and commitment to resolving conflicts through moral reason and kindness,” explains Harman. “And those are types of governance and self-discipline that potlatches also teach.”

In April, Harman co-curated Together Apart, a three-day symposium for 2QS/Indigiqueer folks put on by the grunt gallery, where Harman currently works. “I’d been curating last season’s round of Spark Talks [grunt’s monthly artist talk series] and the basic intention of moving towards Together Apart,” explains Harman, “was to extend the same sentiments I had with the Spark Talks: to make space for 2QS/Indigiqueer folk and to leave a touchstone behind for whatever Indigiqueerdos end up at grunt down the line.” Made up of readings, roundtables, nature walks, musical performances and artist talks — some open to the public and some for 2QS/Indigiqueer participants only — among other things, the symposium was a way for Harman to share their time, resources and empathy with their community, to make space for and give voice to the queer Indigenous population. “Together Apart went really well in many aspects,” they say. “I think, or I hope at least, that the participants felt like things were going smoothly and that they were able to share their work comfortably. Working as an artist, I definitely know what it’s like to feel as though you’re somehow in the way or just how awkward it feels when you’re not totally sure what’s going on or if a space is ready for you.”

In addition to co-curator Kali Spitzer, Harman had some help and guidance in pulling the symposium together. “I looked a lot at a previous event that happened in the early ‘90s called The Two-Spirit Cabaret,” says Harman. “Looking at that archive felt so validating and real because I could see people like me awkwardly doing what I’m also trying to do, and it felt like important evidence of care.”

Care is essential in Harman’s artistic practice. Not only in the care and intention that goes into creating their own work, but in the mutual care of those who surround Harman’s life and work. “Making good work is important, but having good relations with the people who are interested in what you do is just as important and will guide you to making better work. I think the clearest way of figuring that out for me is if I make time for someone and they reciprocate and appreciate that effort, I know I’m going to feel good about the work we do together.”

*