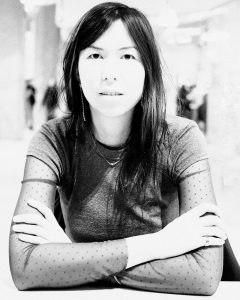

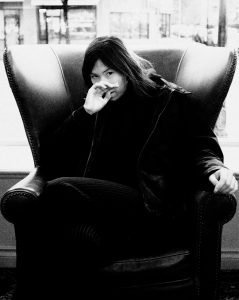

“ddmmyyyy” by Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes appeared at Artspeak, 233 Carrall Street, Vancouver, from November 3 to December 8, 2018.

Years ago, I had a job in the bowels of the Vancouver Museum helping to rearrange a cavernous artifact storage room. Magnificent potlatch feast bowls, rows of old Vancouver street and phone directories, toxic taxidermied bears and mountain goats, E. Pauline Johnson’s death mask. Immersive stuff, artifacts that vibrated history and becoming. But one thing I could not relate to was a homely collection of scrapbooks made by Vancouverites early in the last century. Seemingly arbitrary pictures someone had cut from a catalogue and pasted on oatmeal construction paper. I just could not see the value in them and commented on how artless they were. The curator angrily chastised me for missing the point. “But that’s what people did on a dreary Vancouver night a hundred years ago! They cut out pictures. They pasted them in a book.” Then I started to get it, it was about people making these pictures their own with what they had on hand. It was about people taking images that could have come from anywhere and been made by anyone and making a concrete place for them in their lives, there and then.

Here and now, the question of making the pictures we see resonate with the life we live could not be more pressing. This seems to be the problem Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes takes up in ddmmyyyy, her new photography installation at Artspeak. Even if Holmes doesn’t quite give us a solution, the exhibit suggests that she is happy to take the task of image management quite literally and see where it leads.

A Prius next to a desert bush, the hand of a driver on the wheel of a Lexus, a single bell ringing and a collage of bells echoing through multiple images, a laser cutter, dry grass growing over a metal fence, the hands of someone taking a photo, a spray of blossoms. Holmes doesn’t appear to be presenting these photos as sacrosanct documents so much as negotiating with them. These negotiations involve presenting and displaying images in ways that might give her and her viewers real space to distill their potential meaning or decide if they even hold meaning at all.

The show is made up of eight sets of images presented on four two-sided stands. The stands are modelled after the free-standing chrome sign holders we see every day walking into any store. With this referent, it’s as if Holmes has taken the role that photographs play in reproducing the conditions for commodity fetishism and asks us to reconsider our navigation of image production and dissemination. We’re going to start working out the meaning and value of a picture either by association or disassociation with commodification.

This is where Holmes starts to play, linking her “itinerant images” to customised displays that bear her personal stamp. The vertical chrome bars are set in hand-cast blocks of dyed concrete and attached to picture frames made of strips of stained oak. The more elaborate framing constructions lead the work away from the store display motif into contexts more readily associated with sculptural installations, conjuring associations to alter pieces and reliquary displays. In particular, the clay knobs and flame capping the chrome bars of two pieces suggest funny quasi-art historical referents that may or may not be bum steers. It’s details like these that free us up to take in the image in a different light.

Holmes’s panels could be seen as a proxy for the pictures and graphic ephemera she encounters every day: images with no obvious author, history or provenance, images often seen with no obvious meaning beyond appearance, images that may or may not have crawled out of the sea of stock photos. Even though she took all but two of the photos here, there’s a sense that Holmes has given up on the struggle for authorship of the photographic images themselves, but tries to recover it by crafting the sites where they are displayed.

If this is the case, I have mixed feelings about the tactic, however well it works for this particular show. Some of the “stock photos” here are too aesthetically idiosyncratic and inventive to be relegated to anonymity. Holmes’ photo of a computer terminal in what appears to be an office at Hastings Racecourse is particularly striking and begs for its due in a more conventional setting.

But the show makes its point well – creative tactics are always at hand for negotiating with the roving images that swamp our lives. The more creative we can be about managing these visual encounters, the more breathing space we give ourselves to recognise if they belong in our personal orbit.