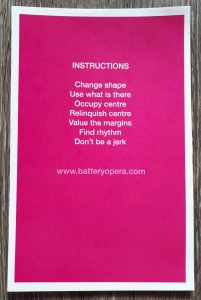

Sadira Rodrigues and Justine Chambers start the conversation, pictured in the photo.

By Arts Reporter Erin Ward

A circle of dancers and artists sit, some in chairs, some on the yellow wood boards of the studio floors, surrounded by mirrors and ballet barres and windows overlooking the city. There are backpacks and water bottles and discarded shoes scattered across the floor and the sound of birds calling to one another from just beyond the panes of glass adds to the ambient sound of chatter in the room. A few more people filter in and find places in the circle before the conversations start to ebb, slowly replaced with expectant silence. They have come to this studio—to this month’s installment of the Talking Thinking Dancing Body series—to join a conversation examining the relationships between dance and art and the institutional and cultural systems in which they are embedded.

I sat down with Lee Su-Feh and Sadira Rodrigues before the Oct. 24 conversation to learn more about the Talking Thinking Dancing Body series. Su-Feh, co-creator of the Battery Opera dance company, explains that she originally developed the series in 2012 as a pedagogical exercise for students of the professional dance training program, Modus Operandi. The conversation has since been opened to the public and has expanded to include Rodrigues, an educator, curator, writer and administrator, and dancer and choreographer Justine Chambers as facilitators.

Su-Feh explains that the facilitated conversations are intended to create a space in which to think critically about dance and art. For her, these artforms are inseparable from the larger social, political and cultural landscape in which they are found, and yet the influence of those systems is often not examined.

“What I often find is that people critique [dance] in this really isolated way, you know, what do I like about the show what do I not like about it. We don’t question or interrogate . . . what happens in our own bodies in reference to the world, in reference to politics; who has power and who doesn’t.”

She points out that dance has historically had an important function in generating and expressing cultural identity, and given this, there has also been a history of politically-motivated suppression of certain forms of dance.

“[D]ance is a serious art form, it’s sacred, it’s political and there’s a long history of dance being so important that governments have felt the need to shut it down. In Canadian history, for example, you see the banning of the potlatch, or the Sun Dance and these are ways to prevent people from telling their stories, or transmitting their oral knowledge. It’s a disruption of their culture.”

While these are examples of outright suppression, there are also more covert forms of restriction. There are power structures within currently accepted forms of dance that define what constitutes dance, who gets to do it, and how they get to do it.

As Rodrigues points out, the restrictions that result extend beyond the forms that dance takes to the bodies of the dancers themselves.

“Dance can sometimes be a strongly hierarchical system and [thinking about what is happening] in the news today in terms of gender relations, there can be significant power relations that play out. [Last year] we talked a lot about questions of consent and how artists can negotiate the full value of the contract, which isn’t just the contract they receive to participate in a dance or in the making of the choreography of a dance, but also this idea of self care, like when you’re asked to do something you’re not comfortable with, your body is not just an instrument that someone can play with.”

While these issues continue to be brought to light and explored, the conversation this year has shifted somewhat to focus on examples that model how artists can address restrictions and enact positive changes. The discussions are meant to empower individual acts on the part of artists that will contribute to a larger shift. Rodrigues explained that the conversations this year are being guided by the metaphor of a landslide.

“To really affect a shift in thinking ultimately requires a landslide where nothing remains unchanged. But the landslide actually occurs by a series of pebbles shifting in the same direction. So while we ultimately want to enact some kind of systemic change, [the way to bring it about is by enabling] artists and dancers to think about how, in their own practice, through a whole range of small actions, they can affect that shift.”

As the Oct. 24 conversation progressed, gently guided by Rodrigues and Chambers, Su-Feh listening from across the circle, the rectangles of sunlight cast across the studio floor slowly changed, growing longer then fading away as the sun moved through the sky. The shifting sunlight seemed a fitting reminder that the world is constantly changing, and that these conversations are part of a change currently underway; part of a movement that is shifting how we understand the role of art in our cultures. This series is one of many pebbles moving in the same direction, small movements that together have the power to start a landslide.

The conversation continues next Tuesday, November 7, 2017, at 5 p.m. at the Scotiabank Dance Centre.