The outbreak of COVID-19 has triggered the practice of social distancing, enforced self-isolation, and quarantining around the world. Consequently, Western capitalist cultures are buckling under the pressure of undervalued healthcare systems, and to provide essentials like housing, safe supply, and universal income. Capitalism has officially failed, and that’s cool and everything, but it is uncomfortable.

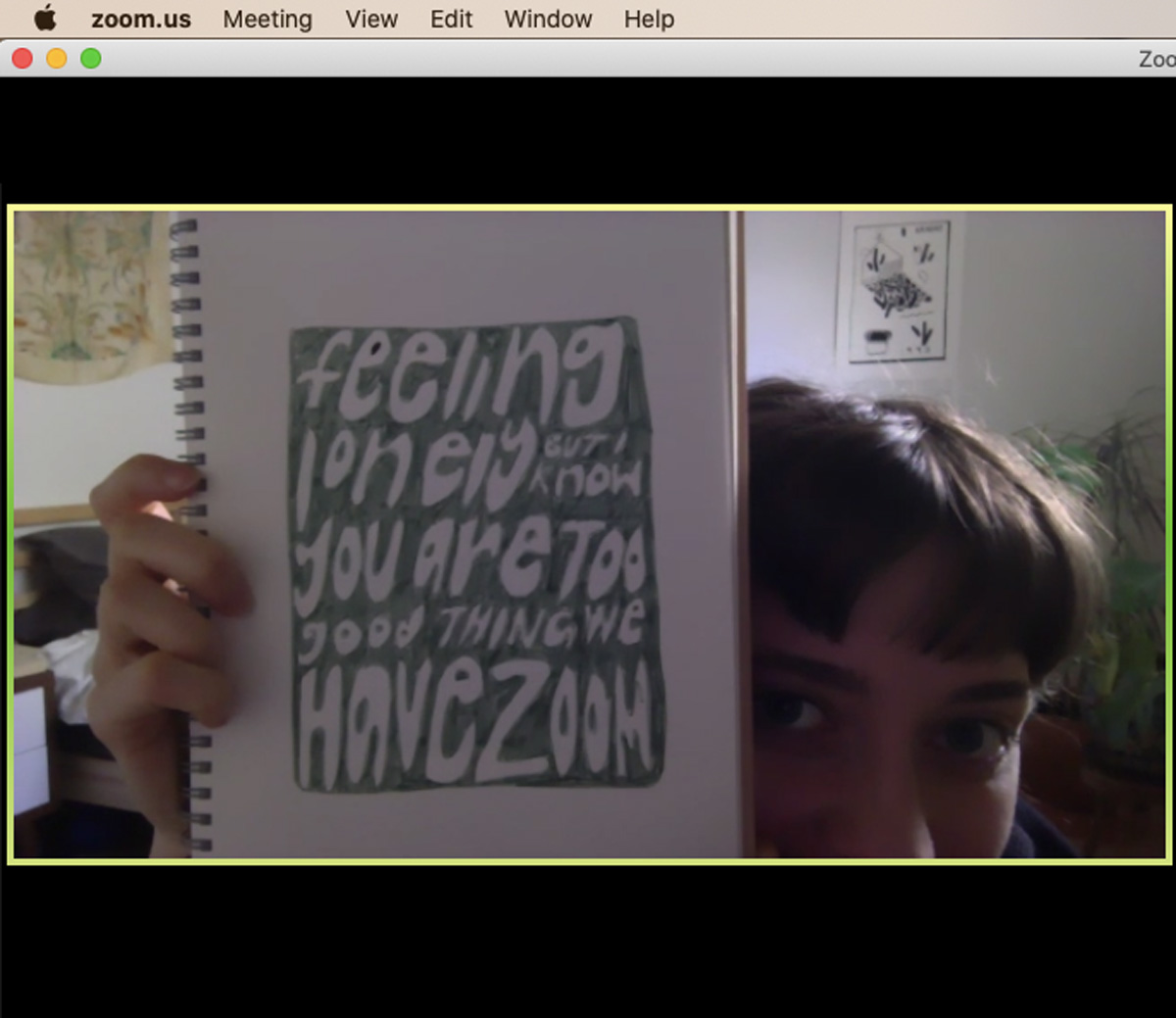

While everyone adjusts to our new reality in their own way, Julia Cundari’s series of small, visualized poems sums up this emotional oxymoron perfectly. The pieces are extremely simple and articulate — bursts of melancholic frustration — and are a strikingly honest articulation of a lot of the fears, anxieties, and insecurities that are driving the narrative of this moment.

I met with Julia on (duh) Zoom and our conversation bounced around easily — covering work, anxieties, fears, and tips on passing the time. “The unknown is scary right now. We’re all living in this state of hyperarousal in the unknown, and searching for outlets that are maybe not satisfying our needs,” Julia pointed out, “and then we feel extra complex because there’s nothing to ground those fears in. The whole outer world is going through this process of change and nobody knows what’s going on.”

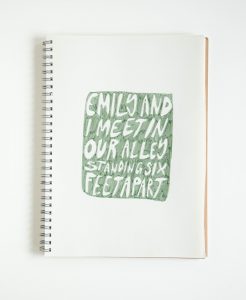

The four text-based pieces that prompted this article read:

“Emily and I meet in our alley / standing six feet apart.”

“I usually spend most of my time alone so this isn’t so bad / but it actually feels kind of bad / my nervous system is on overdrive.”

“I cannot find the time even though / it’s all I have.”

“How do I tell you that I am sad we are not friends.”

The short poems are bubbled across an entire sketchbook page with the background roughly shaded in around the words. Each piece takes about 10 to 15 minutes to make, “which feels like a long time to be ruminating on only a certain set of words.” Julia continued, “I see this as a time to be self-reflexive, but the only way I feel like I can process it is through poetics and writing these words over and over. I feel like it reflects the loop thinking that’s occupying my days.” And the poem’s form mirrors how Julia has been coping with self-isolation, and all the seemingly tectonic adjustments. “I think there’s this whole other side of things, focusing all of my attention on these words and colouring them in really slowly. Spending a lot of time with each tiny poem sort of emulates this slowness that’s happening right now.”

The series names the arguably ubiquitous experiences of young, relatively privileged, and politically progressive art types; a group I will readily admit that I am a part of. “I feel both connected, and disembodied, and reaching for this attachment, but not knowing exactly the most effective way that we can go about feeling that. We’re feeling — or at least I’m feeling — complete opposite feelings all at once.” Julia laughed, “I’m talking in ‘we’s’ and this is something I don’t even do. I’m referring to the entire world as my partner.” Granted, this group is just a sliver of the COVID-19 experience, and one whose complaints, while still very much being felt, are comparatively non-issues. “A lot of them feel kind of whiny.” Julia explained, “They feel very self indulgent but they’re a bit cathartic.” This catharsis has echoes of that hollowness, while honouring the release that comes with sharing without fear of judgement.

What’s exceptional about Julia’s series is their simplicity and clarity. Fear of aloneness, instability, futility, motivation, and distance are embedded in the poetry and communicated directly to the viewer. They read more like snapshot diary entries than public pieces of art, and the access to just one other person’s anxieties — which feel so strikingly familiar — is a small comfort in a time punctuated by upheaval.