What is it that makes music radical? Some music, like Run-D.M.C, Miles Davis’s Kind Of Blue, or the Ramones’ first endeavors into buzzsaw punk come from radical origins, but are gradually assimilated into the culture until it is hard to hear them that way. You have to remind yourself that this music initially sounded wild or mysterious, and represented an alternative to everything that was around at the time. Many sounds that were initially jarring, like the punk played by the Ramones, eventually wind up as whole genres of music, and are subjected to endless rehashing until they no longer have much semblance of the novelty or charm that once made them so pleasurably unique. Other times, a new genre is created, but it doesn’t seem to represent anything particularly novel, or anything that really opposes social or artistic norms. Motley Crue’s Too Fast for Love may be a foundation album in the history of hair metal, but who cares? On the other hand, John Coltrane’s late period albums like Om, and perhaps free jazz in general, still sound oppositional. These sounds never really entered the popular consciousness. Still, it seems to me that novelty does not necessarily make something radical. Some music that is not exactly crucial, nor makes any attempt to reinvent genre, retains its radical qualities over time.

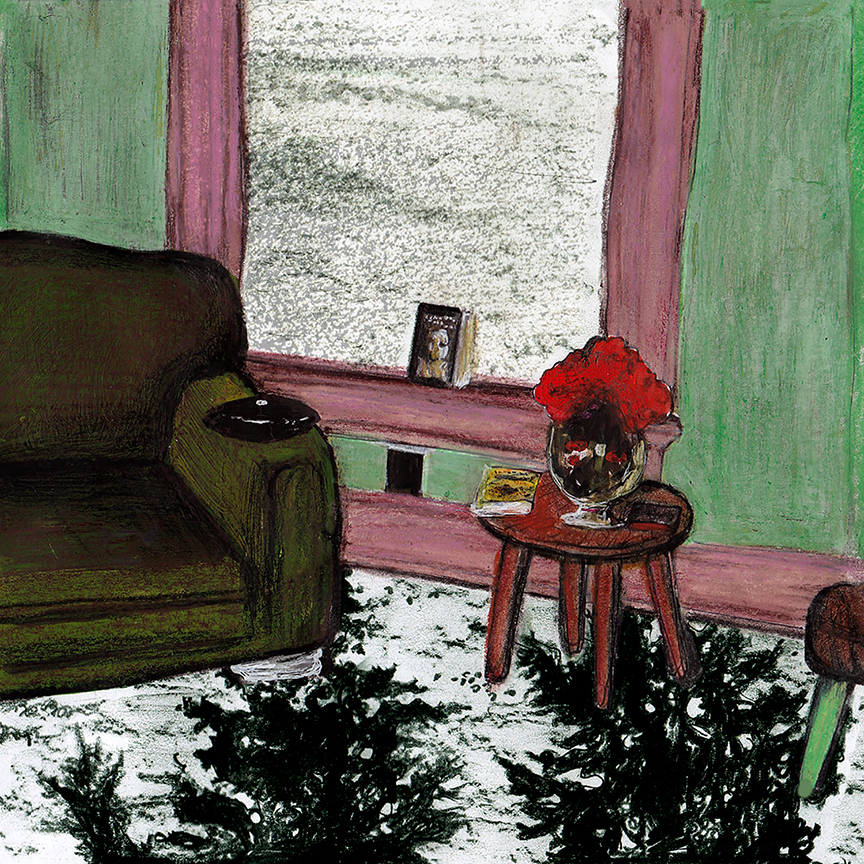

I thought about this recently as I was listening to the new Beat Happening retrospective, Look Around. I got into Beat Happening as a teenager in the CD era. After pirating the song “Godsend” through Napster, I saved my allowance and bought the comprehensive career spanning box set, Crashing Through. Looking back, it seems like kind of a rash move to spend sixty dollars on a box set after hearing only one song. But I loved the song, and I didn’t regret it. Their skeletal brand of pop contained both instantly hummable songs and all of the mysterious vibes of home recording. I remember skipping school to lie on the hardwood floor of my childhood home to let my musical mind be rearranged.

Beat Happening didn’t sound like other music, and they still don’t. Although they employed the standard tools of rock, it was their approach that yielded a singular return. By rejecting musical prowess like punks, but also macho posturing, masculinity, and rock and pop star attitude, they created work that still sounds radical in its humbleness, and still stands outside the bounds of mainstream culture. They also spurned some of the transgressive elements that were popular in the counterculture at the time (some, like Henry Rollins, seemed eager to brush them off as “twee” or “cute”), which made them rebels in all circles. Their minimal approach to songwriting, magical melodic sense, bizarre childlike energy, and subversive lyrical tendencies add up to what I still regard as a distinct and peculiar perspective.

While the work of Beat Happening was radical because it personalized and decontextualized traditional forms, some music aligns itself with non-traditional ideas by using aesthetic qualities that seem unlikely to be absorbed by the culture. It sets itself apart, like Coltrane. I think that Babysitter’s new self-titled 2015 album has some of the personalized weirdness that Beat Happening was dealing in, while also using more abrasive qualities of outsider music gone by to set itself apart. These are disenfranchised anthems paired with free jazz, no-wave inspired skronking and squelching. It varies from song to song, but the overall intent is unmistakable; these people are not concerned with the general acceptance of their music, in the same way that the people who developed these sounds weren’t. The tones of the record are menacing, absurdly hilarious, and nonsensical. This referencing of atypical musical approaches and commitment to an energizing dichotomy of brutish rockism and smart, jazzy musical complexity make for a bracing concoction.

But it’s a strange thing: in 2016, radical musicians can simply exist, build their small audience, and lurk quietly in the background. They won’t be assimilated. But with the liberty granted by the internet, they also don’t have to confront anything in order to exist in the way that Beat Happening did, as ambassadors of the underground. Will radical musicians just go about their business in bizarro mini-utopias? Perhaps this is an effective approach, and perhaps this is how it has always been. But it’s still hard not to affectionately regard the direct, roundly confrontational work of music like Beat Happening.

x